Brief History#

I joined the Stormhaven team in May 2020. This is a project that had started as a passion project by a small group of Everquest fans, had already gone through several personnel shifts through its history, and by the time I joined the project had made some significant progress and had received the funding required to expand the team.

The project, then called Saga of Lucimia, had a solid technological foundation, but still lacked a majority of its key systems both in terms of gameplay and user experience. The game was still somewhat of a proof-of-concept; I was brought on to help bring the game to a release-able state.

Always Shipping#

One unique aspect of this project was that we were developing in full view of a community of players. From before I started and through to release, we shipped changes to our players on a weekly basis. After launch, we adopted a monthly cadence with full and descriptive patch notes provided every month. This cadence has been kept through to today.

Due to this visibility, we were provided with much, often quite vocal, feedback from players and this has helped us course-correct along the way.

Top-to-Bottom Feature Work#

Among myself and our CTO, our working relationship naturally fell into a feature-ownership paradigm. While there’s always times when work overlaps, and we continually consult each other to ensure alignment, we generally pass tasks between us based on who is most familiar with a given system. For the remainder of this article, I’ll be diving into the features I was chiefly responsible for. As such, you can safely assume that I performed the vast majority of programming involved in each system, including: back-end, UI, network communication, and tooling.

Social Features#

Back-End#

When I joined the project, there were only rudimentary social features implemented. The game had an external Python service that handled chat and rudimentary group management. I was tasked with fleshing this out and given my past experience with back-end service development in C#, we decided to build a new service from the ground up for our social features. Given the fact that we already had players engaging with the game, I was also directed to not disrupt the existing JSON-over-TCP protocol the project already had established.

What has followed is now a reliable social service handling server-side logic for the following:

- Chat, with configurable channels, and supports channels for global communication, zone-based communication, group/guild/raid communication as well as world-position based communication (using an in-memory KD Tree)

- Groups, including leader management and seamless restoration in the event of service or connection failure

- Guilds, including ranks, rank-based permissions, general and officer chat, GMGuild Master: the top-most rank in any guild which holds absolute power over the structure of the guild. transfer, etc.

- Raids (comprised of multiple normal groups)

- LFG/LFMLooking For Group / Looking For More: a common abbreviation in genre parlance for the process of formulating a group , allowing players to find and join groups or find new group members based on desired activities and roles

- Friends and Block lists, allowing players to manage 1-to-1 relationships in-game

- Mail, including both the in-game postal service as well as invites for the aforementioned features

- Cross-Zone player status, being the only non-zone-specific back-end we have, the social service also propagates player status changes including social status (Online/Away/Do Not Disturb), role/specialization, level, location, etc.

This service maintains real-time connections with all in-game players over TCP and processes commands sent to it in an asynchronous fashion. It uses a MongoDB server for player data persistence which is shared with the zone servers. It makes heavy use of in-memory caching and pre-caches player data on startup to avoid hammering the database during mass-connection events. Due to the niche nature of our product, we decided to run only a single instance of this service at a time. If we ever need to restart the server while players are connected, the game client will continually try to reconnect them until the server comes back up, when they reconnect, the social service will already have restored all their data and player state from the database and they often won’t have even noticed any service interruption. Naturally, such disruptions are extremely rare.

One construct that emerged during the development of this service and has proven useful time and time again is the use of Broadcast Groups. Broadcast Groups are merely collections referencing in-memory player objects in lists meant to receive communication in bulk. Every in-game group has a Broadcast Group, every guild has three (one for the general roster, one for members that can chat, one for officers), every zone has one, etc. These groups, of course, are primarily used to send chat to players, but they also function as lookup groups for online players. The global Broadcast Group contains all currently online players and is used for global chat but also for general lookup of any online player in a variety of social logic. Likewise, the general guild Broadcast Group is used for looking up online guild members in certain cases as well. Overall, this is a simple concept that has proven to be a useful and reliable way of managing collections of players and forms a central utility that is used throughout the service.

This service is structured in a quasi-standard way for a .NET application. Foundationally, it is an ASP.NET Core application, but the majority of its logic is driven via a BackgroundService implementation which handles the TCP socket connections and delegates to command handlers:

public interface ICommandHandler

{

CommandClass CommandClass { get; }

Task Handle(WorldCommand command, IPlayer sender);

}

These handlers handle basic validation and permission checking logic (which varies greatly for each individual command) and then calls an underlying service layer which handles the doing of the thing (i.e. business logic, if you want to be boring about it). This service layer will in turn either call other services in this layer or call to the provider layer to perform database interaction. In this way, it’s not unlike a million other tiered application structures, but this design was not prescribed, simply emergent.

The following is an example of the guild.kick command:

sequenceDiagram

participant client as Game Client

box Social Service

participant handler as Guild Handler

participant service as Guild Service

participant provider as Guild Provider

end

client->>handler: Send guild.kick command

handler->>handler: Is sender in guild?

handler->>handler: Can sender kick people? (as cached)

handler->>handler: Are they kicking a valid player?

handler->>service: Read Guild and Guild Member records

service->>provider: Read (cache/DB)

provider-->service: Result

service-->handler: Result

handler->>handler: Did we find their guild?

handler->>handler: Is the player they're kicking in this guild?

handler->>handler: Do they really truly have permissions to kick?

handler->>service: RemoveMember()

service->>provider: Remove member from guild in database

provider->>provider: Update in-memory guild cache

provider-->service: Success?

service->>service: Remove member from broadcast groups

service->>client: Notify relevant clients of the kick

service->>service: Log the event

service->>service: Update in-memory player state

The service makes heavy use of dependency injection, including multiple cases where it simply injects everything that implements a certain interface and iterates over them, calling each one (not very impressive, but I just think it’s neat).

Aside from the command handlers, another important ingestion mechanism is the player ping. This ping contains basic information like player position, level, role, etc. Depending on need, there are multiple classes in the service layer which implement IPingHandler and are all informed of every ping received such that they can update any internal state as necessary. This is primarily used for cross-zone player state propagation, but is also used to update our internal KD Tree (used for radius-based chat) amongst other things.

public interface IPingHandler

{

Task HandlePing(IPlayer player, Ping ping);

}

While the service was built as an ASP.NET Core app in anticipation of also exposing HTTP endpoints, this has only been utilized very recently for some internal communication.

Front-End#

The front-end for all our social features resides entirely within our Unity game client. I’ve built a number of UIs for this game including multiple in relation to our social features. In keeping with the codebase as built by our CTO, our social features are coordinated within our game client by a singleton class: the SocialManager. All UIs for our social features react to events exposed by this singleton and call back into it to realize user intent. In pattern-brain lingo, this would be called the view-model.

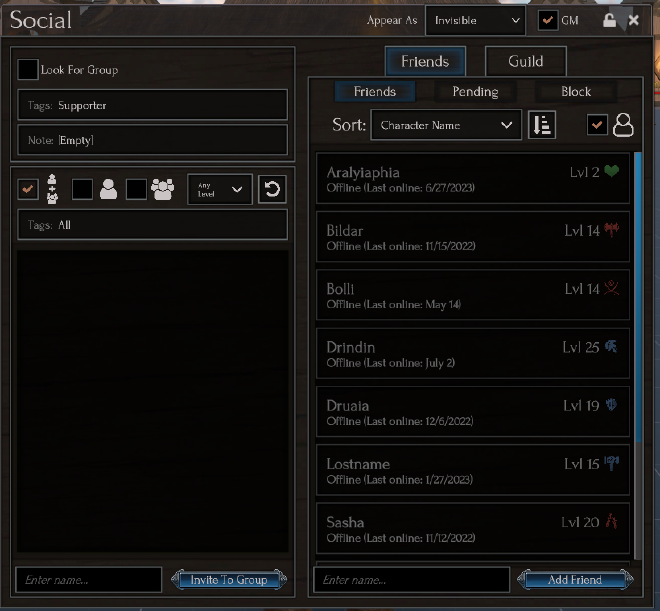

The primary UI that exposes social features is our Social Window, pictured below. This window is divided into two panes: the left pane focuses entirely on the LFG/LFMLooking For Group / Looking For More: a common abbreviation in genre parlance for the process of formulating a group feature. The right-hand pane contains relationship management features. This UI was an exercise in creating a very dense UI full of many interactive features. The design was driven by myself with input from other team members. It’s not a pretty UI, but it’s functional and our users manage to utilize it effectively.

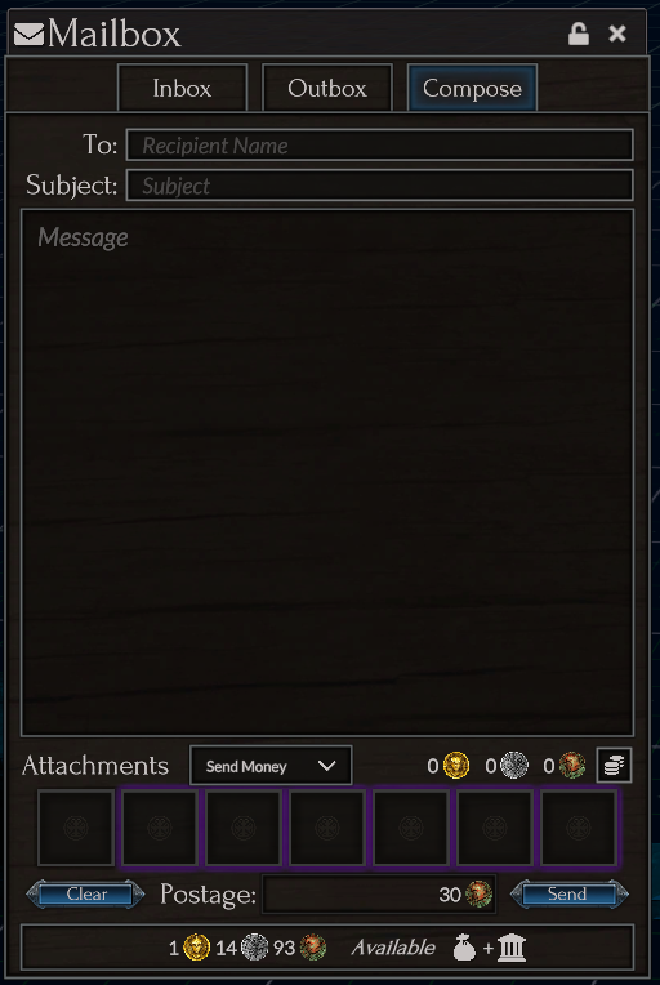

A relatively late feature, the postal system allows players to send messages to each other whether or not the recipient is online. These messages may also send money or items (postage increases based on the items sent). If sending items, the sender also has the option to demand cash on delivery, requiring the recipient to pay a fee before the items are released to them (this fee is sent via another message back to the sender). This postal system was later used to deliver items and cash for our auction house feature (in which I was not involved).

The chat windowing system has been an interesting challenge. In a game like ours, chat is a core feature with many ergonomic expectations our users bring to the table from other similar games. One aspect of the UI that has been interesting to tackle has been: based on any number of situations, which chat window/tab should be activated when the user hits the enter key? This has gone through multiple evolutions over the course of our project, but we’ve landed on the following steps (as of this writing, yet to be released):

- Use the most recently used chat tab, only if active (it’s the selected tab)

- Use the first found active chat tab

- Use the most recently used chat tab, even if inactive

- Use the first found inactive chat tab

- Use the a new chat tab in the most recently active window

- Use the a new chat tab in the first found window

The chat windows are probably the most configurable UI elements. Every player has their own desired configuration and number of windows that must be restored every session. Chat tabs can be dragged between windows, re-ordered in their current window, or dragged out to create a new window. If the last tab in a window is closed or dragged to another window, that window is closed (unless it’s the last window). As you might imagine, this requires fairly particular saving of window state.

Crafting System#

Our crafting system is perhaps a bit overly complex. I was handed a design from early on in the project. It was very ambitious, ultimately a bit too ambitious for the amount of design implementation we were capable of taking on. Nevertheless, the system I built carries out that design intent and over time we’ve been able to utilize some aspects of the system.

Flexible Recipes#

Every recipe in this system requires the fulfillment of one or more components. Each component can be fulfilled by one or more possible materials. For example, a sword recipe might have blade and hilt components. The blade component might allow one of any number of possible metals. The chosen material usually affects the stats of the resulting item in some way a designer defines via our tooling. After we implemented this, I noticed that World of Warcraft brought in a similar feature, so we must’ve been on to something with this.

Multi-Step Crafting#

While we only make limited use of this, one of the original pillars of the system was that if a crafted item is used in a later recipe to create yet another item, the original item’s materials can affect the end item’s stats. Essentially, any materials used in the entire history of an item’s crafting history can affect its current stats. To do this, every item instance carries a tree of IDs to track its crafting history such that we can reconstruct the item when it enters gameplay scope.

Data and Tooling#

The item system was originally designed with the notion that items would have fixed definitions (which we term Archetypes). With a crafting system where each item can have an enormous number of permutations based on its own bespoke history, there was no way we could define the plurality of Archetypes necessary to account for every minute difference. As such, I came up with the concept of a DynamicArchetype.

When an item enters gameplay scope, a DynamicArchetype is fetched from a pool and copies the stats of the original item, then applies any one of a number of ComponentEffects as defined by its designer. These ComponentEffects have conditions and actions defined such that they only take effect when the item history contains certain characteristics and, if suitable, they apply any number of actions which alter the item’s stats. When the item leaves gameplay scope, the DynamicArchetype is returned to the pool. This is true on both the current zone server and the client, though the scopes differ.

Even this would be a bit too much design work for a game of this genre. To mitigate this, we have ComponentEffectProfiles which are collections of component effects that can be applied to items. These can also refer to other ComponentEffectProfiles such that the designer can build a composable collection of effects for like items.

Between the recipes, the items, and the ComponentEffects, there are a ridiculous multitude of options available to the designer. This plethora of options has only expanded over time as the designer primarily responsible for our game’s item progression has discovered new ways to flex our system. A few of those options are as follows:

- Recipes can ditch item history and produce something with no history

- Recipes can output entirely different items based on certain criteria (material levels, player levels, components used, etc.)

- Recipes can have a chance of failure and output a “failure item”

- Recipes can output variable quantities of items based on certain factors

- In addition to stats, component effects can alter the item name, multiple aspects of its appearance, requirements, etc.

The design work utilizing our crafting system was largely handled independently by one of our designers with occasional improvements provided by myself as needed.

Quest System#

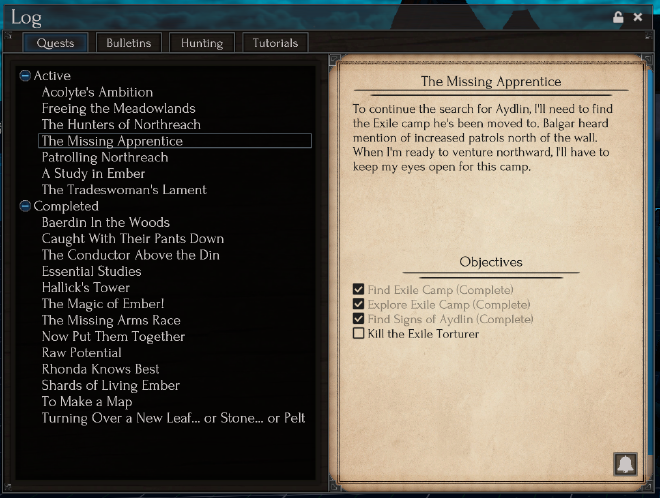

The quest system we built was likewise ambitious, but I feel we’ve made good use of it. This system utilizes ink-driven dialogue scripts, albeit with heavy custom instrumentation. Our quests can freely branch and converge, can have multiple starts and/or multiple endings. They can have a multiple requirements to start, including requiring the completion of other quests. Over time we’ve expanded the number of types of quest objectives the player may complete some of which have quite the range of parameters.

Data and Tooling#

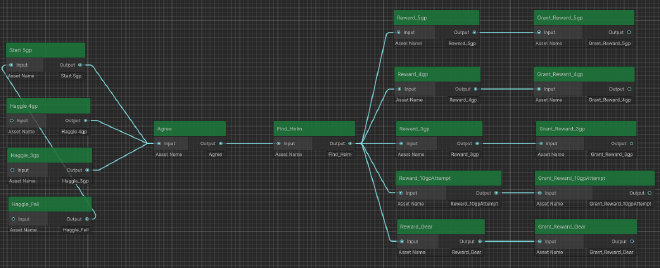

Authoring a quest starts with the writers. They will write dialogue for each part of a quest in one or more ink files, utilizing a light amount of logic to react to certain aspects of game state. Once written, the ink files are passed to me to implement in-editor (we don’t bother forcing our writers to learn how to use Unity, or git for that matter). In Unity, I use a custom graph editor UI to outline the various quest steps and how a player can progress from one to the other. I construct quest objective objects and populate them and the quest data with any specifics not defined in the ink files, including when to pull what dialogue from said ink files.

===BETTY_INPROGRESS

=DIALOGUE

What's on your mind?

*{not HAS_LOOT("HIDES")} Where did you say I could find the Chunks of Rat Fur you're looking for?

I've heard they can be found just outside the wall in Northreach. They're also known to infest ruins all around the region.

->DONE

*{HAS_LOOT("HIDES")} I've gathered half a dozen Chunks of Rat Fur. Will these do?

Oh yes! These will do just fine. Thank you for gathering them. Now, let's see about getting you something for your troubles. #OBJECTIVE=HIDES #RESTART

->DONE

Design Observations#

Our quest system is certainly more advanced than most games in the genre. Whether or not that’s a good thing is still an open question in my mind. One directive I was given early on from the rest of the team was that we wanted a branching quest system. In hindsight, such a system may be better suited to single-player RPGs than multiplayer RPGs like ours. While I’m proud of what we’ve built, I wonder whether a system that forces players to live with their choices might be in conflict with how most players play MMOs. Most players in an MMO value hyper-optimization of their characters, likely driven by wanting to perform at their best when working with other players. If they feel that a branching quest has locked them out of getting a specific item they perceive as critical to their character build, they would understandably be upset. We’ve done our best to ensure that quests with different endings have equivalent rewards, but this may not be enough in this regard.

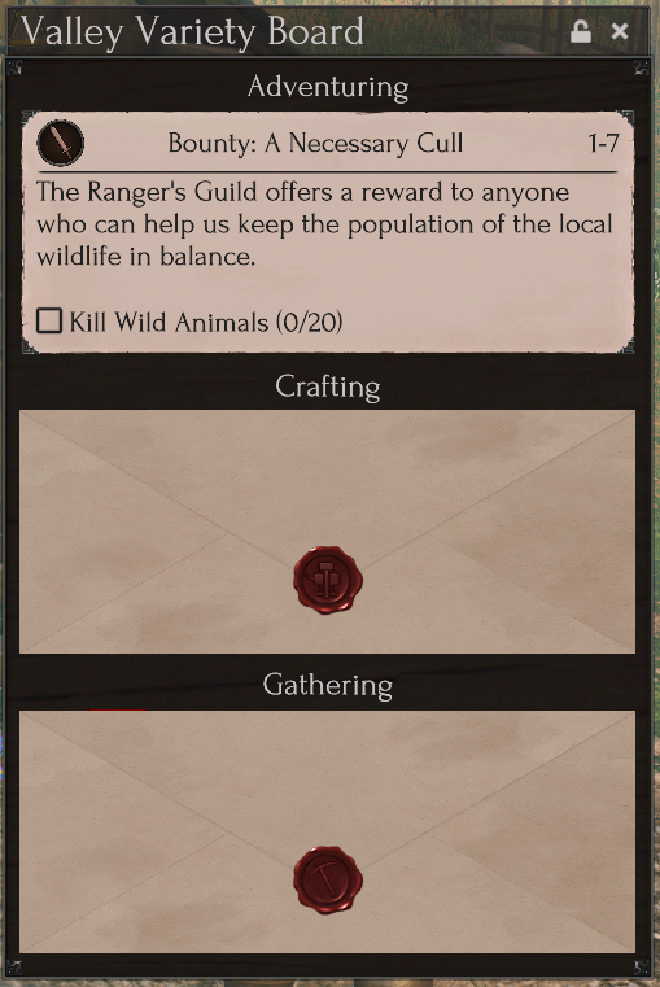

Bulletin Boards#

In addition to the quest system, we added a system for bite-sized quests that are purely solo-able and offer a small bit of experience. This system utilizes much of the same logic as quests, particularly the quest objectives, but they are both collected and turned in at bulletin boards, not through character dialogue like quests usually are.

The tasks assigned by bulletin boards are somewhat random. Tasks are chosen based on character level, whether they’ve been done before in this session, what category they chose, and in some cases, their class or profession.

Also, the envelopes/cards design was my idea. 😀

Other#

- Monitored logging and player reports to find and address problems as they arose, including multiple investigations to determine whether certain events were caused by logic errors or player behavior

- Keyboard/Mouse rebinding system: pretty standard fare allowing free rebinding including key combinations

- Tutorials: early on in the game, when players take certain actions or reach certain checkpoints, tutorial popups will appear to help explain certain systems (these tutorials can all be reviewed in the tutorial log)

- Notifications: Alerts players to mail or invites with a notification toast on the right-hand side of their screen, missed notifications appear in a window they can open (which is highlighted when it contains notifications)