Rationale#

In an effort to understand ECS designs and their relation to data-oriented design, I decided to undertake a project to implement an ECS design. I did not follow any particular tutorial. Rather, this implementation is loosely based on my understanding of other implementations but does not emulate any particular one. As such, this project is my attempt to deduce an implementation based on that high-level understanding, specifically in order to connect that to my understanding of performance-related topics. This means that my primary concerns were keeping component data contiguous in memory and prioritizing quick and largely branchless iteration over that data in the critical path.

Memory Layout#

I’ll try not to give a lecture on ECS here, but in short, the memory layout I pursued for components in the original C version of this project was based on the concept of archetypes as they are defined in Unity DOTS. What this means is that component data is split into pools based on “archetype,” i.e. entities that use all the same components will have their component data stored together. So, component data overall is split firstly based on what component it is and secondly by archetype. This can be contrasted with the layout many ECS solutions employ, and the one I employ in the C++ rewrite, where component data is only split by component and all entities have representation in that one segment of memory. Neither of these methods is better than the other in all cases.

Storing data by archetype is more complex and has some runtime downsides depending on application behavior. For instance, you end up having to move a bunch of memory around in that design whenever your application modifies what components are associated with a given entity (which, by definition, changes its archetype). Also, below a certain number of entities, splitting up your data by archetype will naturally result in smaller segments of data, making data less contiguous and therefor less efficient to operate on. On the flipside, a global component storage method will result in more contiguous but more sparsely utilized data. This may be acceptable depending on how you iterate over that data or if you don’t have a very large and diverse set of entities.

In addition, I’ve found that not all data fits neatly into per-entity components. This may seem obvious, but some data is more useful in a global context. However, I wanted to preserve data dependencies (for system dispatch reasons as explained below), so I opted to store this data in “scratch” segments. These segments are referred to by the systems operating on them in much the same way systems refer to component data, just handled slightly differently. This is very loosely inspired by the “singleton components” described in the GDC talk about Overwatch’s architecture.

System Processing#

Systems are run via worker thread task scheduling (using a third-party single-header task scheduling library) and dispatched in accordance with their stated dependencies such that systems that read data other systems write are run after those other systems. Systems that do not depend on each other may run in parallel (I would say “concurrently” here, but I don’t want to run afoul of the pedantically illiterate parallelism vs concurrency dichotomy).

From what I know of other ECS implementations, it seems like most of them handle iteration over component data outside the system logic and pass component data for an individual entity into the system for processing. Perhaps this is a misunderstanding, but I found it more sensible to pass the entire array of component data into the system and allowing the system to determine how best to iterate over the data. This allows systems to, for example, utilize SIMD during iteration to handle processing of said data in bulk. I could be missing something very clever here, but this seems like something only the specific system logic itself can determine, so this seems like a missed opportunity in those other implementations (which is also why I question whether I’m understanding those implementations properly). In any case, while I don’t have too many systems implemented at this point, there are a couple where I utilize SIMD intrinsics depending on what the CPU supports. They currently support AVX512F, AVX, and SSE as an initial implementation. I expect to expand to other instruction sets if/when they become necessary, including those of non-x86 ISAs such as NEON. If none of the aforementioned instruction sets are supported, these systems will of course fall back to a plain for loop. It has also occurred to me that it might be good to move these systems out to a shared library so I can compile for multiple instruction sets and load them as needed at runtime as a form of dynamic dispatch, but I’ll get to that if it ever becomes a priority.

int system_move2d_exec(ComponentStore *components, float deltaTime, uint32_t threadNum)

{

TracyFunc;

float *px = components->Position2D.Pool().X;

float *py = components->Position2D.Pool().Y;

float *vx = components->Velocity2D.Pool().X;

float *vy = components->Velocity2D.Pool().Y;

ComponentIndex ix = 0, iy = 0;

ComponentIndex length = components->Capacity();

#if defined(__i386__) || defined(__x86_64__)

#if defined(__AVX512F__)

ComponentIndex len16 = (length / 16) * 16;

length = length % 16;

__m512 dt512 = _mm512_set1_ps(deltaTime);

for(; ix < len16; ix += 16){

_mm512_store_ps(&px[ix], _mm512_add_ps(_mm512_load_ps(&px[ix]), _mm512_mul_ps(_mm512_load_ps(&vx[ix]), dt512)));

}

for(; iy < len16; iy += 16){

_mm512_store_ps(&py[iy], _mm512_add_ps(_mm512_load_ps(&py[iy]), _mm512_mul_ps(_mm512_load_ps(&vy[iy]), dt512)));

}

#elif defined(__AVX__)

ComponentIndex len8 = (length / 8) * 8;

length = length % 8;

__m256 dt256 = _mm256_set1_ps(deltaTime);

for(; ix < len8; ix += 8){

_mm256_store_ps(&px[ix], _mm256_add_ps(_mm256_load_ps(&px[ix]), _mm256_mul_ps(_mm256_load_ps(&vx[ix]), dt256)));

}

for(; iy < len8; iy += 8){

_mm256_store_ps(&py[iy], _mm256_add_ps(_mm256_load_ps(&py[iy]), _mm256_mul_ps(_mm256_load_ps(&vy[iy]), dt256)));

}

#else

ComponentIndex len4 = (length / 4) * 4;

length = length % 4;

__m128 dt128 = _mm_set1_ps(deltaTime);

for(; ix < len4; ix += 4){

_mm_store_ps(&px[ix], _mm_add_ps(_mm_load_ps(&px[ix]), _mm_mul_ps(_mm_load_ps(&vx[ix]), dt128)));

}

for(; iy < len4; iy += 4){

_mm_store_ps(&py[iy], _mm_add_ps(_mm_load_ps(&py[iy]), _mm_mul_ps(_mm_load_ps(&vy[iy]), dt128)));

}

#endif

#endif // defined(__i386__) || defined(__x86_64__)

// Naive onesy-twosy

for(; ix < length; ++ix){

px[ix] += vx[ix] * deltaTime;

}

for(; iy < length; ++iy){

py[iy] += vy[iy] * deltaTime;

}

return 0;

}

Re-Inventing the Wheel#

While this isn’t the first project where I’ve done such things, I did place some focus on building some of my core utilities from scratch. Things like allocators, collection classes and a custom string class. This was primarily in an effort to more closely control when and how certain objects and their underlying data are allocated. For strings, they utilize an underlying global pool. Other collections can vary, but I’ve made a lot of use of my frame allocator (an arena allocator cleared once per frame). These systems have only somewhat been proven out, and I have yet to really put them to the test, I feel. Which leads me to:

To Be Continued#

This experiment is far from over. This really needs a full game implemented in this system to really illustrate for me the full effects of this design. Unfortunately, with Stormhaven no longer able to pay me, my employment situation has taken priority (including setting up this site). I’d like to continue it later, but until I can rationalize spending time on such things again, it will likely sit idle.

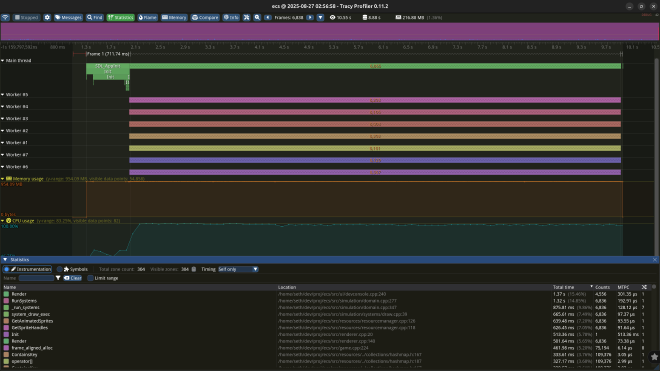

However, I will say this project has been useful in allowing me to grasp much of the very low level implementation concerns with such a system and this is also the first project where I’ve used the Tracy profiler (pictured above), which I’ve very much enjoyed putting to use.